Virginity, used to describe a total lack of sexual experience – particularly intercourse – has held a massive cultural significance for millennia. Long prized as a symbol of purity, the demand for virginity was often used as a way of valuing or devaluing women while also sometimes serving as a source of ridicule for sexually inexperienced men. In modern times, many societies have fortunately revisited this focus on virginity and the norms of sexual experience, recognising that sexual history can be diverse and that it need not be used to shame anyone.

However, data on when certain populations make their sexual debut can still be a useful metric of sexual health and social attitudes in general. While there are some international organisations, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), that track data about sexual behaviour around the world, generally in-depth studies are only performed within a single country – and the United States has some of the most comprehensive data available.

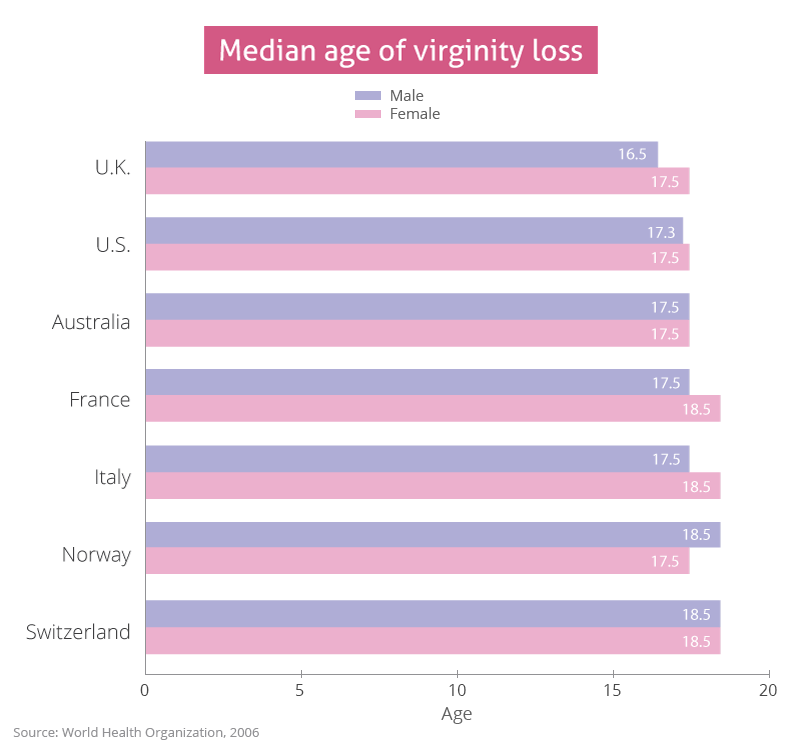

According to a WHO paper published in the prestigious health journal The Lancet, the U.S. is near the middle of developed countries in terms of the median age at which males lose their virginity, 17.3 years of age, and near the lower end for females at 17.5 years.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control conducts the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) every few years to track the sexual behaviours of Americans. The NSFG interviews over 10,000 males and females between the ages of 15 and 44, asking hundreds of questions and ending up with over 3,000 variables for each respondent.

This detailed data offers a valuable look at the many factors affecting a population’s sexual health - sadly, no raw datasets from the UK have yet been made available to the public. So we looked at this massive data set to identify trends in virginity loss among the American population. Read on, and learn about the factors influencing people during their first sexual experience.

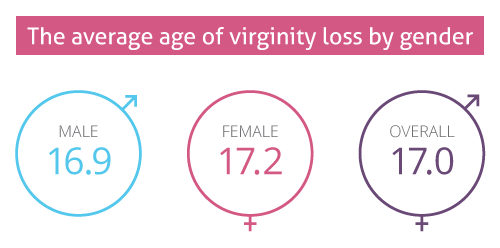

1. THE AVERAGE AGE OF VIRGINITY LOSS BY GENDER

The overall average age of virginity loss, according to the NSFG, is 17.0 years old, slightly less than the WHO’s reported 17.3 years. However, WHO only tracked people between 45 and 49 years of age in 2006. The average age of any event that happens once per lifetime (such as loss of virginity) increases as respondents get older, for a very good reason: People to whom it hasn’t happened don’t get counted.

The average age of loss of virginity for NSFG respondents who are 15 years old is 13.8, because all of the people who are still virgins – about 80% of them – aren’t counted, as they have no age of virginity loss to be averaged. On the other hand, for 44-year-olds, the average is 17.7 years, just a few months higher than the overall average because at that point there are very few virgins not being counted. For these reasons, a more useful metric might be the number of people per each age who are still virgins.

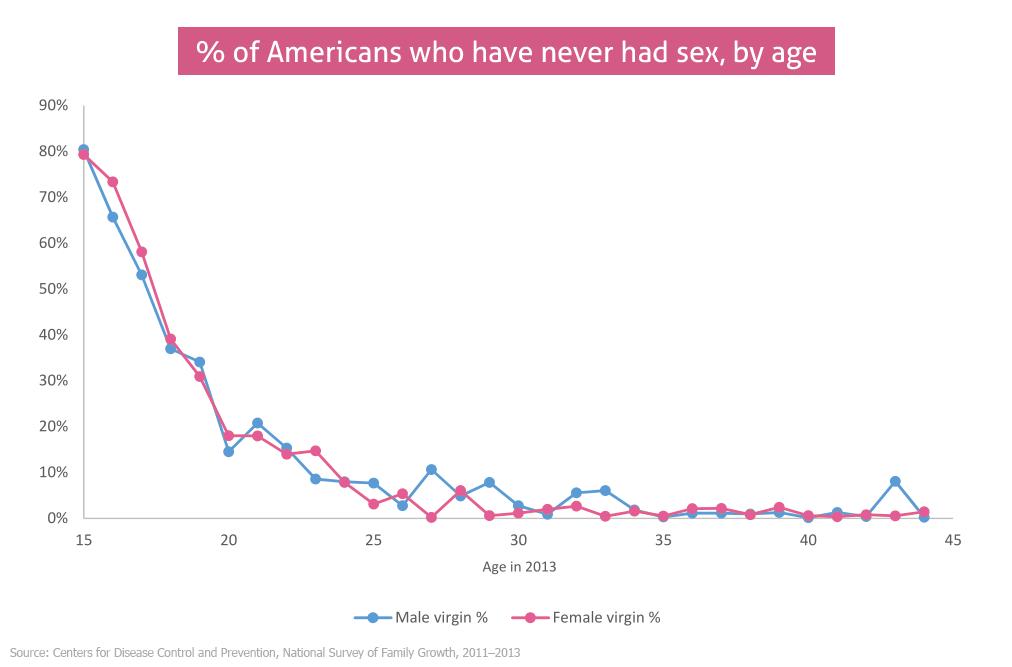

2. PROPORTION OF VIRGINS AT DIFFERENT AGES

The lower age of virginity loss among males as described above is most visible on this graph between 15 and 18 years of age, where the blue points are consistently below the red points.

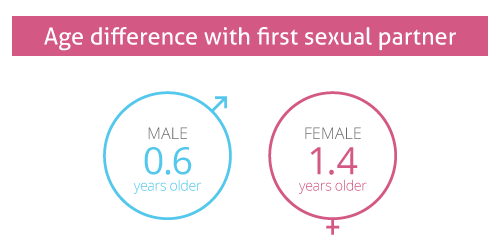

3. AGE DIFFERENCE WITH FIRST SEXUAL PARTNER

Overall, males’ first sexual experiences tend to be with women just six months older than them, while females’ are typically with men nearly a year and a half older.

This might seem like a logical inconsistency, until you realise that it’s common for people to be the first sexual partner of more than one other person, and just because it’s one person’s first sexual experience doesn’t mean it’s also their partner’s first. The NSFG doesn’t track this specifically, but it’s a reasonable explanation for why most people’s first sexual partners tend to be older. For instance, John could be 17 when he loses his virginity to his then-girlfriend, 18-year-old Jane. John and Jane may break up, at which point John would begin dating 16-year-old Mary, who then loses her virginity to John.

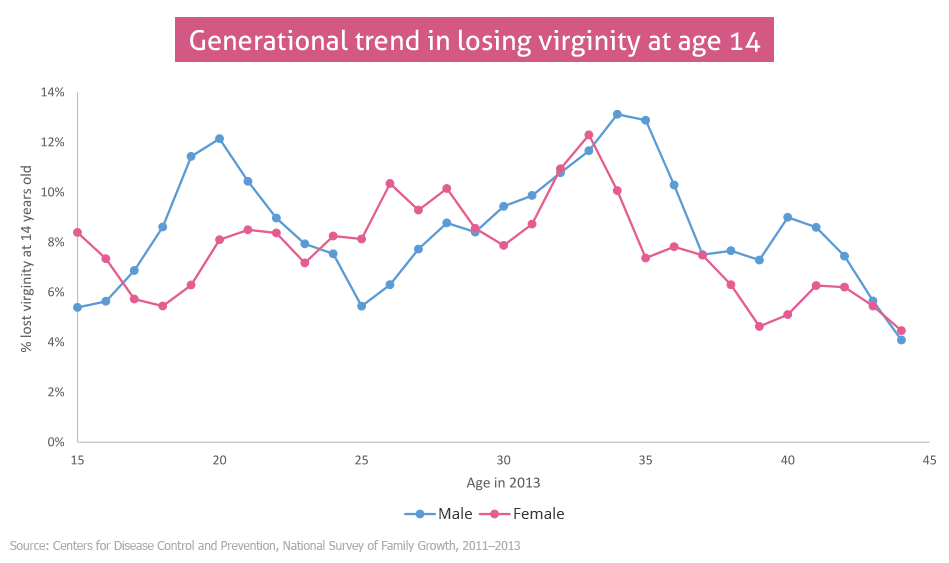

4. GENERATIONAL TREND

Kids today are certainly exposed to more sexually explicit material than 10, 20, or 30 years ago, both due to an increase in sexual scenes on television and greater availability of new media via devices such as smartphones. From 1998 to 2005, the amount of sexual scenes on television reportedly almost doubled, (https://www.kff.org/other/event/sex-on-tv-4/) and youth are now typically exposed to over 4 hours of television every day. (https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/influence-new-media-adolescent-sexual-health-evidence-and-opportunities) Does this translate into earlier loss of virginity? Surprisingly, it appears that this hasn’t substantially changed.

Unfortunately, we can’t use the age virginity is lost to compare different ages because, as explained above, older people will always lose their virginity at a higher age on average than younger people, as the few virgins remaining add their ages when they enter the pool. A useful proxy is to compare the percentage of people who lose their virginity at an age that is below that of everyone in the survey – for example, 14 years old. While there are changes from year to year, they trend upward and downward and are most likely due to sampling errors. There’s little visible difference between people who are now in their 40s and people who are now in their teens nor is there a consistent difference in trends between males and females.

5. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH AGE AT LOSS OF VIRGINITY

We used a statistical technique to identify which factors had the strongest effect on the age when respondents had sex for the first time. This required caution: Some factors, such as marital status, are actually so closely coupled to the age of the respondent (older people are more likely to be married or divorced) that they would only show older people always losing their virginity at a higher age, on average, than younger people. We also eliminated factors that are too closely coupled with the age of virginity loss - for instance, females who were pregnant in their teens were more likely to have lost their virginity earlier.

So we were left with several factors that, regardless of age and independent of the variable we’re studying, significantly influenced the age distribution of virginity loss among Americans aged 15–44.

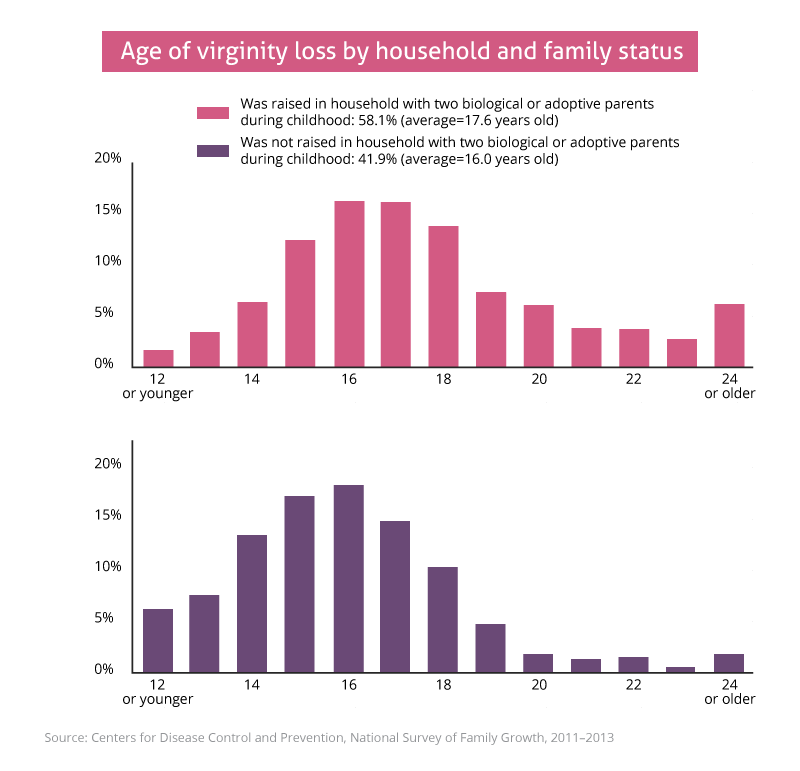

One of the factors that was tied to the strongest shift in age of virginity loss was whether the respondent did or did not grow up in a household with the same two biological or adoptive parents throughout their childhood. The graph above shows the distribution of the members of each set among the different ages. About 6% of those who did not grow up in a two-parent household lost their virginity at age 12 or younger, an age at which legal consent is not possible, while those living in a two-parent household lost their virginity at this age only about 2% of the time. While the figures on virginity loss at such a young age may seem shockingly high, they reflect the overall prevalence of non-consensual sex reported by all survey respondents: 15.2% of women experienced involuntary sex with men, while 4.7% of men experienced involuntary sex with women. The distribution of ages for each group shows a clear pattern: People growing up in households with two-parent families are likely to lose their virginities at an older age, while those not living with two-parent families are more likely to lose their virginity at a younger age.

It is important to note this is a correlation, not a clear example of causation. We can’t say that growing up in a household with two parents directly causes people to lose their virginity at a later age. There may be hidden variables tied to both of the factors we are studying. For example, it could be possible that stricter parents cause teens to have sex later because the consequences of getting caught are greater. These stricter parents could, for cultural or moral reasons, be more likely to remain together as a two-parent household, and teenagers are less likely to lose their virginity when their parents clearly disapprove of them having sex (http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9068.html). It is very difficult to determine causality from this kind of data, and one should be careful to refrain from making moral judgments based on it.

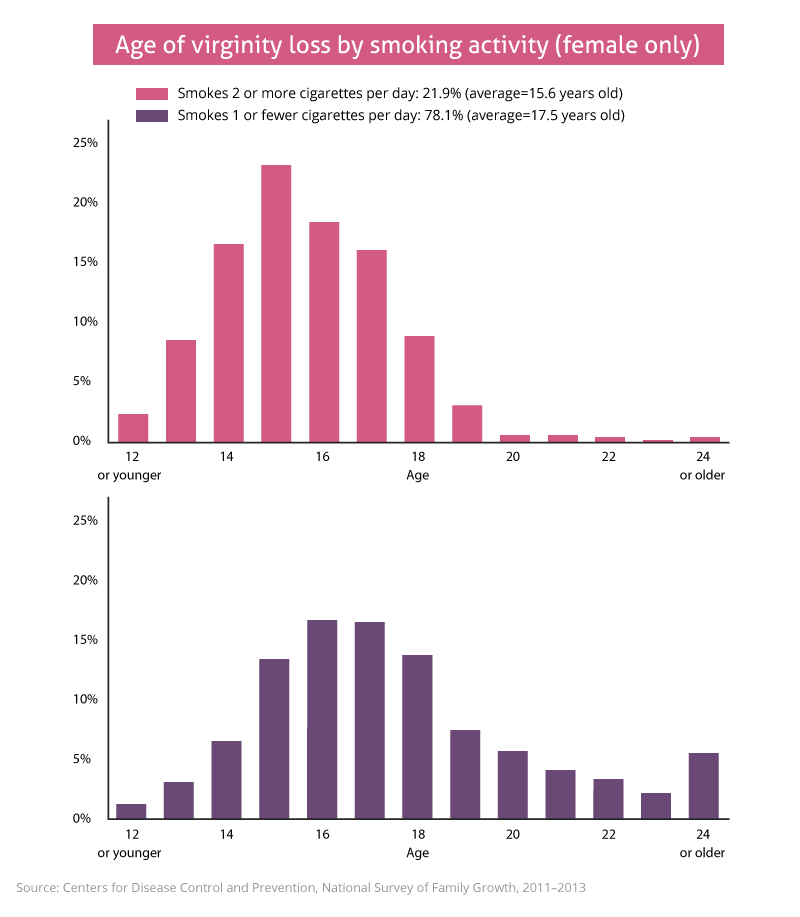

Another variable that’s most correlated with a different distribution of age of virginity loss is whether the respondent smokes, if female. (The NSFG didn’t ask that question of males, presumably because it’s only a gender-related issue for females due to the risks it can pose during pregnancy.) For frequent smokers, the distribution is shifted much further to the left and is much narrower in time frame: They tend to have sex for the first time almost two years earlier than infrequent smokers or non-smokers. You may notice that the smoking rate (21.9%) is high compared to the CDC’s estimate of 15.3% for adult women, but this is because the definition of smoking and the age distribution of the studies are slightly different. It’s also worth noting that the study did not look at whether the respondent was smoking at the time of the virginity loss but rather in the year before the survey was conducted.

Here, it’s especially obvious that we’re dealing with correlation and not causation. It’s implausible to think that smoking causes virginity loss or vice versa – the most we can say is that maybe people who smoke are risk-takers in other ways.

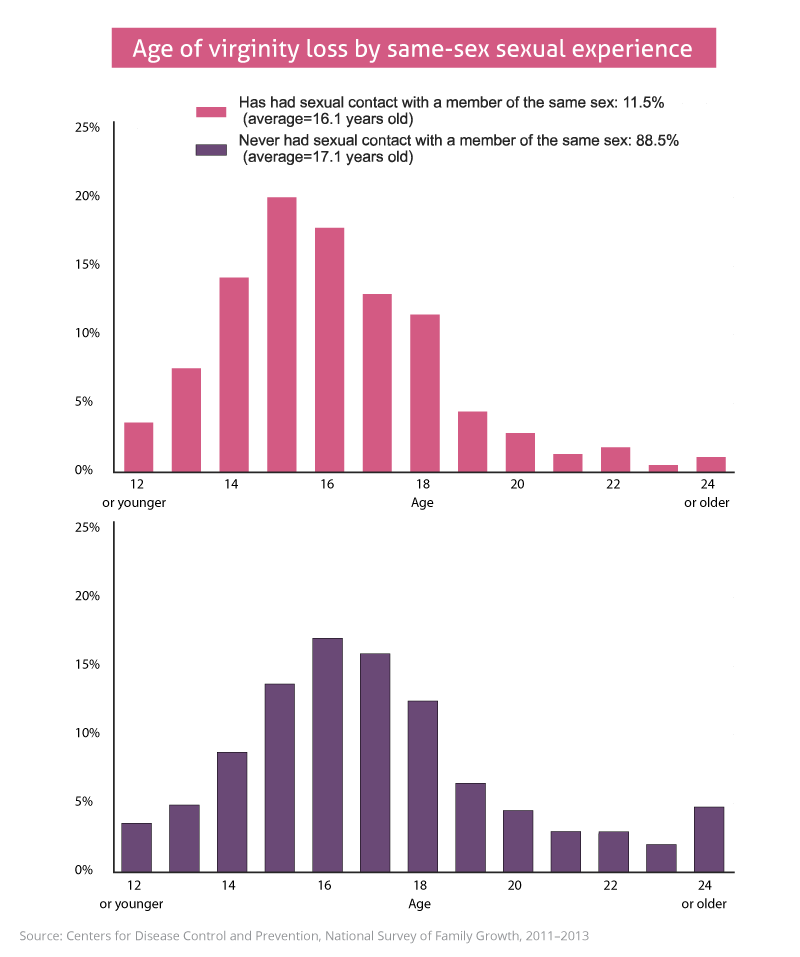

When we measure something, it’s important to know exactly what we’re measuring. In this case, the variable used by the NSFG to define virginity loss is whether the respondent had heterosexual vaginal intercourse, which is the traditional meaning of a loss of virginity. Interestingly, those who have had at least one instance of sexual contact with a member of the same sex also tend to have heterosexual sex earlier. The total number of people who have ever had a same-sex sexual contact, 11.5%, is roughly in line with a later re-evaluation of the Kinsey Reports, a historical study of same-sex sexual behaviour in the U.S.

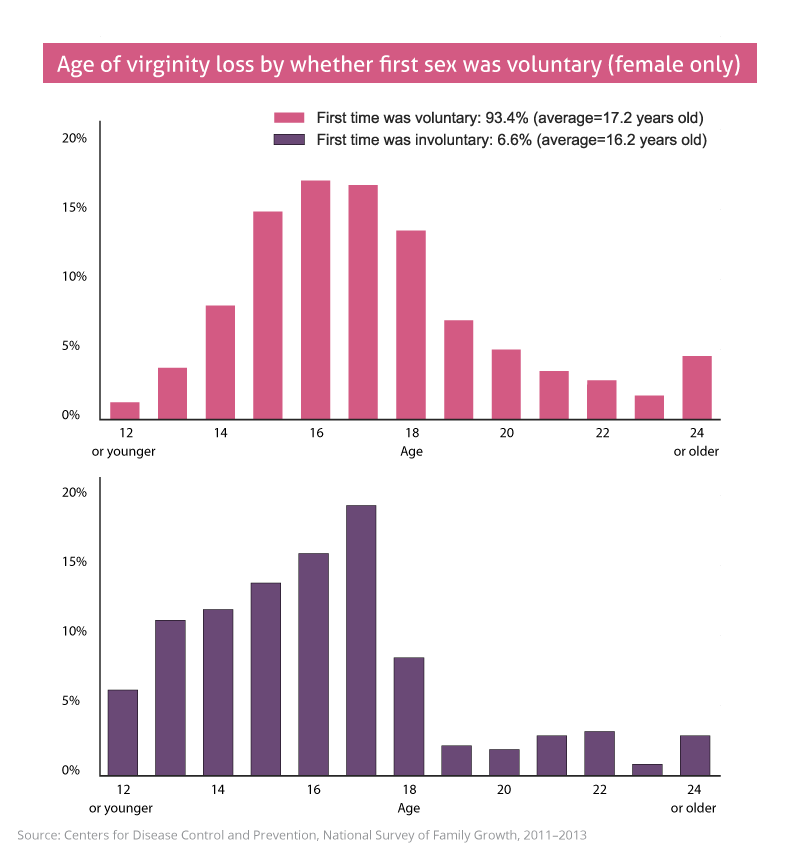

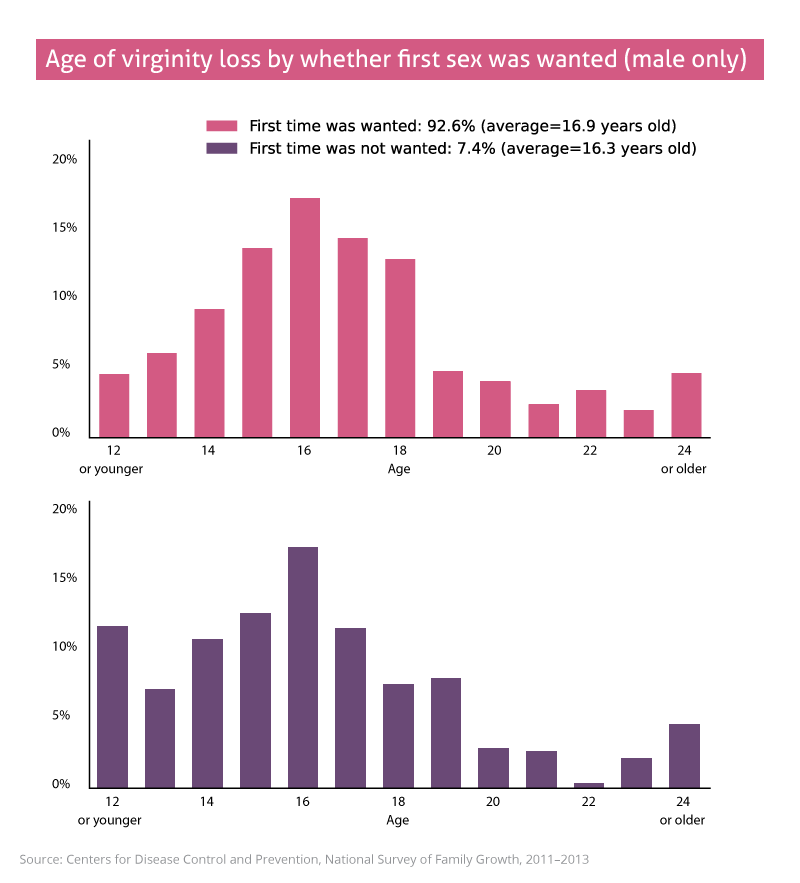

Unfortunately, not everyone’s first time is consensual, and the NSFG asked whether female respondents felt that their first times were voluntary. “Involuntary” includes use of force or any sort of overt coercion.

Here, we see the effect of this variable is restricted to the youngest ages, which makes sense, as it’s plausible that younger people are more vulnerable to coercion. After the age of 14, the bars for each group are intermittently higher or lower, indicating no consistent effect.

The NSFG also posed such a question for males, with slightly different phrasing, asking if the first time they had sex it was “wanted” (rather than “voluntary”). This may have been intended to elicit a more accurate response, as many men may not feel comfortable describing sex as “involuntary” due to the connotation of rape. Ultimately, the results remain very similar. The difference is most visible below the age of 15: Most respondents whose first experience was at age 14 or younger say that it was unwanted.

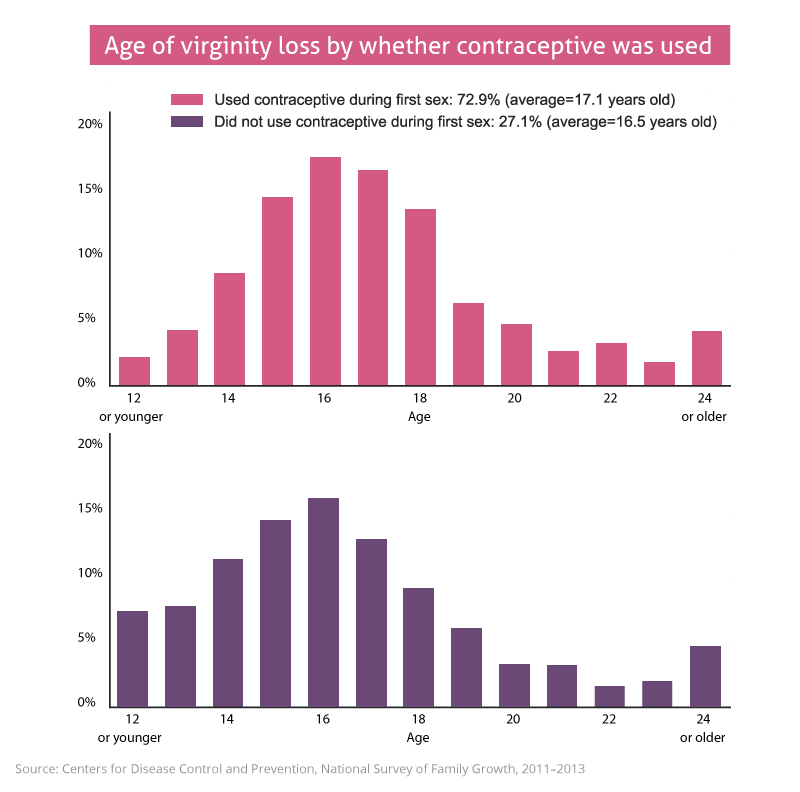

Another example of an effect only visible in the youngest ages is that of whether the respondent used any form of contraception their first time – and alarmingly, over a quarter of respondents didn’t. Here, it’s the youngest people who were the least likely to protect themselves. While it’s difficult to identify specific causes contributing to this pattern, these findings show a need for greater education of youth and access to contraception.

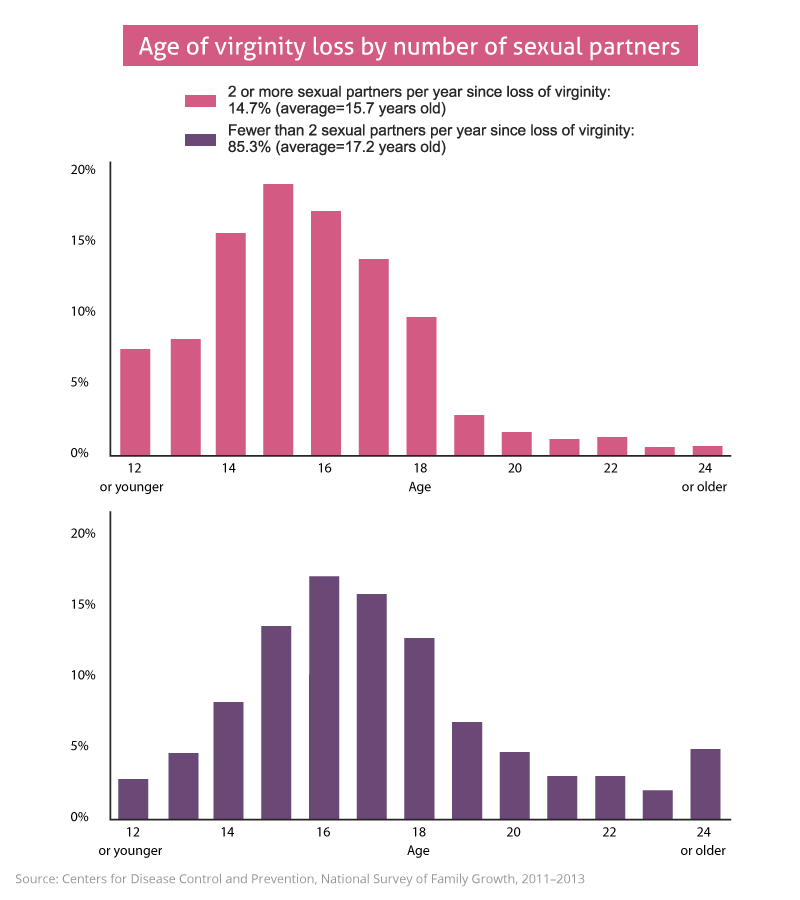

Interestingly, one factor that’s tied to the distribution of age of virginity loss occurs after said loss: how many sexual partners the respondent has had between that event and the survey interview. Those who have had, on average, two or more partners per year are those who lost their virginities earlier than those who had fewer partners. Again, it should be stressed that no causal relationship can be inferred from this.

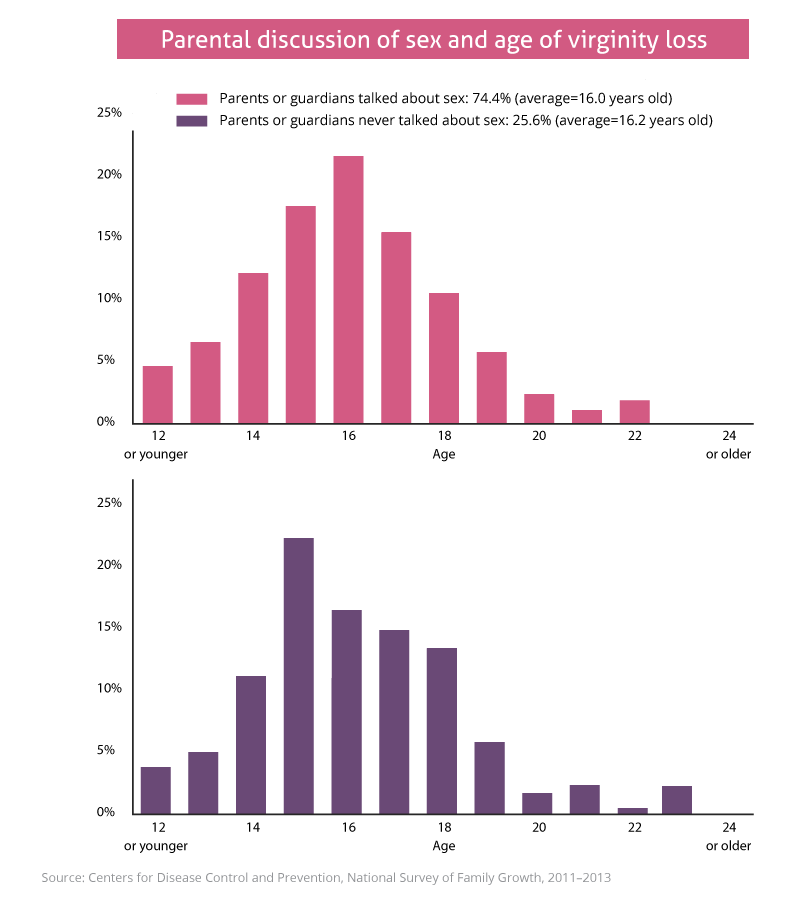

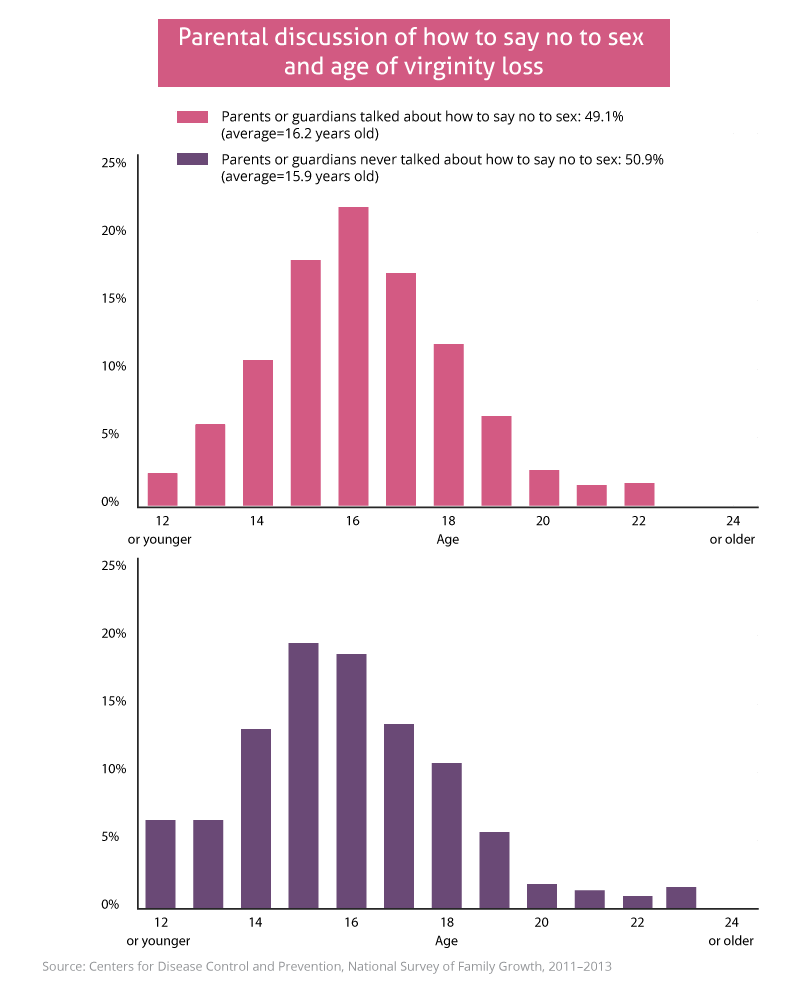

Interestingly, whether parents or guardians talk about sex with their children does not appear to correlate significantly with the age of first sexual experience. While the distributions are different, each group peaks intermittently across ages, showing no consistent effect. But when the question is changed to ask whether parents specifically talk about the issue of how to say no to sex, the picture changes substantially.

Now there appears to be a real difference, especially at the youngest age, although the difference is not as great as some other factors we’ve seen. The distribution of age of virginity loss for those whose parents talked about saying no to sex is clearly and consistently shifted to the right, whereas at ages 15 and younger, those whose parents didn’t talk to them about this are more likely to lose their virginity.

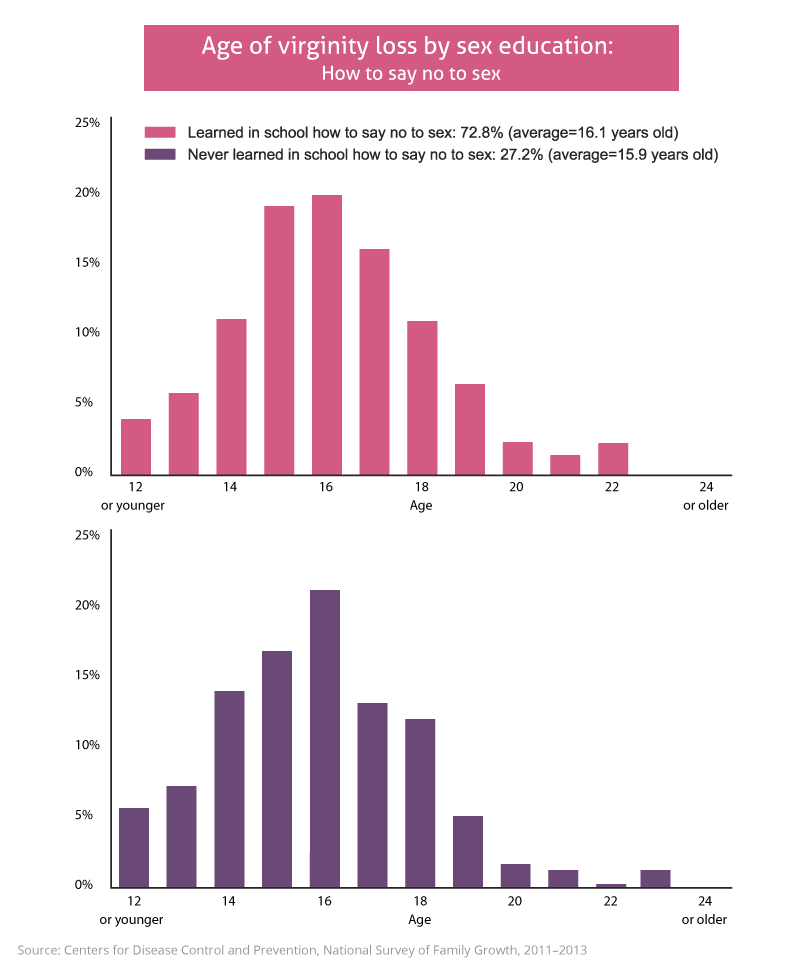

And it isn’t just a matter of the child being informed by anyone. If we look at whether a school program taught them how to say no to sex, rather than their parents, we’re back to seeing a smaller effect:

CONFIDENTIAL AND PROFESSIONAL ADVICE FOR YOUR PERSONAL QUESTIONS

Questions of sex and sexual experience are a culturally charged and yet intensely personal topic, and it can be difficult for anyone to feel comfortable discussing uncertainties. Yet these can also be some of the most important enquiries, with the potential to have a substantial impact on one’s health, well-being, and personal confidence. If you’re looking for help with sexual issues or questions, OnlineDoctor.Superdrug.com is ready to offer the professional, private help you deserve. With certified doctors available to answer your questions, you can find help in the comfort of your home. Visit OnlineDoctor.Superdrug.com, and empower yourself to take control of your health.

METHODOLOGY

Superdrug commissioned us (Fractl) to conduct the analysis of raw data from NSFG 2011–2013 as a basis for these charts. The respondents are weighted as to how representative they are of the U.S. population; we used these weights in every calculation. The survey has certain questions that are only asked based on responses to other questions, so we made sure to identify and only use variables that were applicable to every respondent (either based on questions asked to every respondent or calculated variables based on groups of questions that, between then, were asked of every respondent). Two-way ANOVA was used to identify the factors that most changed the distribution of the age of virginity loss. Factors that were correlated with the age of the respondent were discarded.

SOURCES

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2011_2013_puf.htm

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(06)69479-8/fulltext

- https://kinseyinstitute.org/research/index.php

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/influence-new-media-adolescent-sexual-health-evidence-and-opportunities

- https://www.kff.org/other/event/sex-on-tv-4/

FAIR USE

Feel free to share the images found on this page freely. When doing so, we ask that you please attribute its creators by providing a link back to this page so your readers can learn more about this research and view other available graphics.